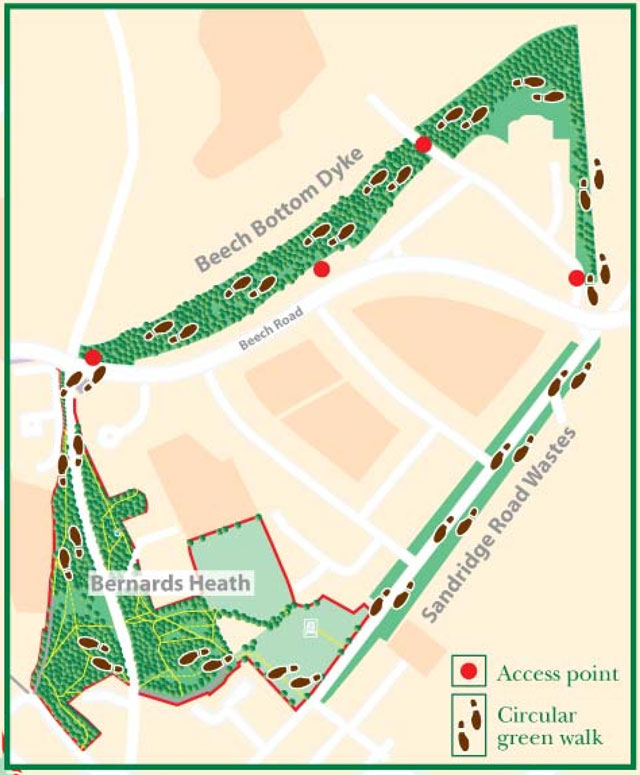

Entrances to the main part of the dyke – to the top of its southern bank only – are marked by red dots on the map below. They are off the western end of Beech Road (north side), down a track on Beech Road near the junction with Firbank Road, from Valley Road where it crosses the dyke and from the north-eastern corner of the Valley Road housing estate open space up against the railway embankment (with a footpath running down alongside the estate to this access). There is no access to the dyke from the north and no footpath along the top of its northern bank. In the past the bottom of the dyke was readily passable, but it is now a difficult scramble up and down and only at the Harpenden Road entrance. The footpath along the top of the southern bank can be challenging in places, especially in wet weather. A visit taking due care is highly recommended, though, and more than repays the effort.

The western tail of the dyke (marked running off to the left) is beside Batchwood Drive and has a pavement along its bottom.

The Dyke

Beech Bottom Dyke is a major ancient earth work to the north of St Albans. It later formed the northern boundary of the historic area of commons called Bernards Heath. This heath was also the main battlefield of the Second Battle of St Albans (1461, Wars of the Roses). The dyke is a Scheduled Ancient Monument (SAM) under the aegis of Historic England HE) and owned and managed by St Albans District Council (SADC). It is St Albans’ most undervalued and hidden heritage asset. One reason is that so much about it is unknown. There is no datable archaeology to help us with when it was built. This guide presents speculations rather than answers about its origins and purpose – but visit it and make your own minds up.

As with almost everything else about the dyke, the origin of its name is uncertain. There are two main theories but no hard evidence. The first theory is that the “Beech” in its name may share its derivation with the nearby “Batchwood”, and the second is that it does commemorate the historic presence of beech trees there.

There were inconclusive archaeological investigations by Sir Mortimer Wheeler in the 1930s, but generally it has not produced any finds of interest. Like so many such monuments it raises questions that cannot be fully answered. This remains the case in the most recent comprehensive study of St Albans’ archaeology (Rosalind Niblett and Isobel Thompson, “Alban’s Buried Towns”, Oxbow Books, 2005) as well as on the Historic Environment Record. (See also the addendum below). There is far more speculation than fact attached to the dyke, and the theories are a lot more entertaining that the few current scientific certainties.

Conventional archaeological wisdom speculates that it was constructed in the period between the two Roman invasions of 54 BC and 43 AD. The leading local tribe then was the Catuvellauni and the period would be consistent with it being commissioned by King Cunobelin (who comes down to us as Shakespeare’s Cymberlaine). That said, there are suggestions that it is early as the Bronze Age and as late the early Roman period, when it may have been part of the defence works for Roman Verulamium. The only real date we have is a Roman coin hoard found in it in 1932 showing that it must have been built by 120AD and site of the hoard filled in by then.

There are also rival theories as to whether it is a free-standing monument or part of a much larger Iron Age landscape between St Albans and Wheathampstead. Was it left incomplete and meant to be joined up with the Devil’s Dyke in Wheathampstead? This is a very appealing idea on the map, but there is no evidence either way and there are rival theories as to whether the two dykes were built at the same time or hundreds of years apart.

There is even dispute as to how large it is. Some claim that the dyke is solely the excavation we can still see today running from Townsend Drive to St Albans Road in Sandridge (and this is the length of the protected SAM). Others maintain that whole original work may have run for about one and three quarter miles – or three kilometres – from the River Ver in the west to what is now St Albans Road (and via Everlasting Lane). By this theory it connected the Ver Valley with the valley running through Sandridge. The parts we can see would be the parts that needed excavation to make a more even route, and not the whole construction.

There is hope that archaeology might still be able to resolve some of these questions with new scientific techniques that do not need massive earth moving. They might tell us if there was any major soil disturbance between Townsend Drive and the Ver (and, in particular, if the Romans filled in some of the dyke there to help with their own roads), exactly how deep the original bottom was – and if it was the same depth along its whole length – and whether the original bottom was on a level with the River Ver. Then we would be sure of its length and route and at least some features of its construction. These data might suggest some answers if they can be researched.

At its most impressive the excavation was about 100 ft wide and 80 ft deep, although some of its depth has been lost over the centuries and most parts are now smaller.

Chris Reynolds in his “Short History of Bernards Heath” indicates a possible route for the Roman road to Colchester (via Braughing) on the top of the southern bank of the dyke. Sometime in the Middle Ages the dyke became a sunken road as a possible continuation of Everlasting Lane. From other early records, the top of the southern bank would most likely have been surmounted by a stock-proof hawthorn hedge.

Between 797 and 1539 the dyke was owned and managed by the Abbey of St Albans. To continue the story of ownership, after the dissolution of the monasteries it passed to the Rowlatt, then the Jennings and then the Spencer families (via the Duke of Marlborough). The current owner of the freehold interest in the land is St Albans District Council when it was passed to them from the Spencer Estate in 1932. (This date coincides with Sir Mortimer Wheeler’s investigations of it).

Its moment of glory was in 1461 at the Second Battle of St Albans (Wars of the Roses). It was incorporated into the Yorkist field defences in preparation for an attack from the north by the Lancastrians. The Yorkist commander (the Earl of Warwick – Warwick the Kingmaker) stationed troops along the dyke, positioned artillery on it, strengthened the hedge with naval anti-boarding nets (with iron spikes woven into them) and sowed a field of caltrops behind it – caltrops being three iron spikes twisted together so that one point always faced upwards to create the medieval equivalent of a mine field. Horses could not cross an area sown with caltrops and one Lancastrian knight (Andrew Trollop) impaled his foot on a caltrop in the fighting near the dyke.

For Warwick, though, this had all been in vain because the Lancastrians cunningly attacked from the south so that his defences faced the wrong way. The battle has left one legacy in terms of modern folk lore. This is that many of the fallen in the battle – perhaps even thousands – were tipped into the dyke and now lie underneath the railway embankment that cuts across it. This is not in fact the most likely burial place, but it is too good a story not to retell.

The land to the south of the dyke was enclosed for arable farming in the late 17th century. The dyke was filled in at what is now Valley Road for easier access to the farmland. By the 1843 Sandridge Parish Tithe Map, the dyke had been planted (and land in it rented out) for coppicing. This is probably the origin of most of the native tree species now there. These include hornbeam and beech for coppicing as well as Scots pine, larch and others. From the air the dyke shows as a strip of woodland.

In the 19th century the dyke was pressed into military service again in anticipation of an invasion by the French. In 1859 the stretch of the dyke from near Harpenden Road to about where Firbank Road now starts was converted into a rifle range and some work may have been carried out to widen and flatten the bottom (by reference to the rear cover picture). A new cut was made into the dyke direct to this longest straight section of it. This explains the strange dips in the footpath near the Ancient Briton, where the new cut was made. At the target end earth was cut from the southern bank and piled into the dyke to its full height and width to form a new bank and another a new access was made (at Firbank Road). It has been alleged that the earth platform at the end of the new access was a (horribly exposed) viewing platform built near the targets. This is another good story attached to the dyke, but it seems implausible even by Victorian Health and Safety standards. In any case, the platform was made in the 20th century. There is a lovely water colour of the local yeomanry at target practice in the dyke (back cover). The description of the boundary of the newly formed St Saviour’s parish in 1904 listed the shooting range as a defining local feature.

In 1863 the Midland Railway Company gained Parliament’s consent to run a railway line across Bernards Heath. The line was built in 1866-8. It slices through the dyke in a dramatic manner before passing through the most likely site for Warwick’s camp with a cut and cover tunnel at the King William IV pub. There were reports at the time in the local press of exciting finds from the battle including skeletons, armour, weapons and coins. None were ever authenticated and they all disappeared without trace in the early 20th century.

The dyke is now valued for its biodiversity and as a green corridor. It is still home to a rabbit warren probably established by the Norman abbots of St Albans Abbey. A rabbit – perhaps from the dyke – was publicly hanged in the Market Place during the Peasants Revolt in 1381 as a gesture of defiance against the Abbey.

The dyke is freely open to the public at all times, but signage is now outdated and access is problematic for long stretches. There is a challenging footpath along the length of the southern bank. At present the bottom of the dyke is only accessible with difficulty from the Harpenden Road end. The picture at the end if this guide shows the bottom fully accessible. With a break a few years ago, there have been community clear-ups to keep the floor passable. Although the SAM status means that this needs to be done with caution, FOBH has resumed this work.

The SAM status gives the dyke the highest level of heritage protection and forbids any ground disturbance – including metal detecting. Nothing can be done that would prejudice the heritage or archaeological potential of the site or act to change its historic setting or its form as it was at the time it was first scheduled (as opposed to built). FOBH as the and the Battlefields Trust are in discussion with SADC and HE about what opportunities there might still be for improving access and signage despite the SAM constraints.

As a footnote to the SAM status, all the mature native trees in the dyke enjoy a status equivalent to Tree Preservation Orders.

Archaeological Speculations

The dyke attracts passionate debate and speculation. There have been several rival interpretations over the centuries and on up to the present. These are presented uncritically and for the local colour they bring to the monument.

Local antiquarians in the 17th and 18th centuries suggested two explanations. The first was that the dyke was an Ancient British chariot racing track, with its even floor and banks for spectators. The second was that it was a way of concealing a road from prying eyes. Sadly for these theories, the original bottom of the dyke may have been a V shape, and, as a hidden road, it goes from nowhere to nowhere.

There has always been speculation that it might have served a military purpose. In other words, it is a military field work. The latest date suggested for it might allow it to be an outlying defence of the Roman city of Verulamium. Sir Mortimer Wheeler left some notes speculating on a military explanation, but found no evidence and did not follow it up. When Warwick the Kingmaker did try to use it as a military fieldwork in 1461, it was a dismal failure. The obvious flaw in the military value of the excavated sections is that an enemy could just march round them at either end. Nonetheless, this still remains an attractive explanation even if needing more work – for example on what was on the ground between Townsend Drive and the River Ver when it was built. A defence system that rested on the Ver would need to be taken more seriously.

There is another school of thought that all the archaeologists have got all their datings wrong and that all the earthworks to the north of St Albans are part of one coherent pre-Roman landscape built at the same time and to a single purpose. One proposed purpose is that the various banks and dykes up to the Devil’s Dyke at Wheathampstead were a complex in-land waterway system designed to link the rivers Ver and Lee. Setting aside the dating issue, this has the regrettable flaw that the two rivers run at significantly different heights above sea level – thus perhaps allowing the earliest known white-water rafting down the dyke.

Many such earthworks have been described as boundary markers – Offa’s Dyke being the prime example. This theory has not been propounded for Beech Bottom Dyke, probably because it so obviously ran through the middle of an existing territory and not along its border. That said, this was how Sir Mortimer Wheeler marked it up on his maps and sketches, but probably because it was such obvious conventional wisdom at the time.

Another idea is that it was simply a prestige project. The point of building it was that it could be built – and to impress friends and enemies alike.

A final standard interpretation of otherwise inexplicable ancient earthworks is that they had a religious or ceremonial function. It might be worth revisiting this explanation if there is more data in the future about the exact size and construction of the dyke. If, for example, it turned out that the bottom was exactly level for its whole length – and that it could be flooded from the River Ver – then a religious or ceremonial use might be more of an option than it seems from a visual inspection of the excavated sections today.

Opportunities and Threats

The easternmost part of the dyke cut off by the railway line has already been filled in (in 1929) and lost, although its route is still obvious running up to St Albans Road.

The biggest opportunity for the surviving parts is to open them up and interpret them, and to include them in the “green ring” of foot and cycle paths round the district. This would have to be handled sensitively to comply with its status as an SAM, but the relevant bodies are in discussion about this. The dyke is St Albans’ most under-rated and undiscovered heritage asset. It cries out for more visitors.

The Friends of Bernards Heath and the Battlefields Trust both run guided walks that include the dyke. This is a positive recent development.

New uncontrolled tree growth is likely to become an ever greater problem. The dyke would benefit from a comprehensive tree survey to catalogue the mature native trees. Clearing out new (particularly non-native) growth would open up views.

Over the centuries the floor of the excavated part of the dyke has been steadily building up. By the beginning of the 21st century some ten feet of depth had been lost. This process is accelerating rapidly with fly-tipping and disposal of garden refuse from adjoining gardens.

Some adjoining owners may be ignorant of the dyke’s statutory status and their obligations not to take actions to prejudice it. Any large scale encroaching development would be picked up and headed off in the planning process, but smaller scale developments in gardens do not trigger this safeguard. The District Council as local planning authority, and Historic England through its local inspector of ancient monuments, are now monitoring the dyke more closely.

There also seems to have been some unauthorized felling of mature trees in the dyke, and this, again, is a matter for the District Council.

Bodies with an Interest in the Dyke

- St Albans District Council – as owner, the local planning and open spaces authority and as agent for English Heritage.

- Historic England – as guardian of its status as an SAM.

- Hertfordshire County Council – as keeper of the Historic Environment Record and through its Countryside Management Service.

- Friends of Bernards Heath – as the local amenity society for the dyke..

- Battlefields Trust – for the dyke as part of a battlefield.

- St Albans and Hertfordshire Architectural and Archaeological Society and the Civic Society – as the heritage amenity societies for St Albans.

© Peter Burley 2016.

With thanks to Roger Miles and Mike North for presenting their work on the dyke to the St Albans and Herts. Architectural & Archaeological Society on 11 March 2014 and to Roger for correcting my mistakes. With thanks also to Chris Reynolds for his “Short History of Bernards Heath”.

In May 2013 Simon West (SADC District Archaeologist) published a re-evaluation of the dyke as an appendix to a consultation on its future. This is set out here with his kind permission.

The Dyke System of St Albans City and District1

ADDENDUM

Summary

The City and District of St Albans has three major phases of dykes or large ditches. The first probably dates to the Middle Iron Age at ‘The Aubrey’s’; the second, a large site at Wheathampstead between the Slad and Devils Dyke dates to the Caesarian period, and finally, at the very end of the Iron Age and into the Roman period, the development of an oppidum [or large Iron Age settlement] at Verlamion. Together these probably span the 500 years from c. 400BC to c. 100AD.

Simplistically, the three phases can typologically be split into two. The first two sites appear to be enclosures, a local defensive response, whereas, the oppidum is much more territorial in its defensive outlook. However, this simple explanation underestimates the place that these massive earthworks played in the social dynamics of the time.

The greater part of our understanding of the larger dykes relies on excavations undertaken by Mortimer Wheeler in the 1930’s. Since that time, little has occurred on the main monuments, but recent work has taken place on various lesser landscape features, such as the ‘Wheeler Ditch’ which ran across the King Harry Lane Playing Field development, as well as the similar contour ditch at the Folly Lane ceremonial site.

The lack of recent excavation of the larger features has meant that the date for the construction of these is for the most part indeterminate, but probably occurs in the last decades of the first century BC through into the middle of the first century AD. The Dykes may have been used by the incoming Romans to define the territorium of Verulamium and as enhanced defences for their city. The dating of the lesser landscape features, although equally significant in themselves, suggest this same time frame. Presumably the lesser ditches would have been secondary to the primary dykes and used as linking features.

Verlamion

From around 25BC a new dyke/ditch system defining the oppidum of Verlamion develops; a small part of which was to become the Roman town of Verulamium. Verulamium Park equates to approximately one-half of the third largest Roman city in Britain2, by the end of the third century AD the city amounted to 80 hectares. The Roman city appears to have used the centre of the Late Iron Age oppidum as its focus, with the Forum/Basilica apparently located within the Late Iron Age central enclosure, with the later larger walled Roman town probably using pre-existing dykes/ditches on the south-west and southern sides. The largest single dyke of this system is Beech Bottom dyke (Wheeler, 18-19) which proved to be 100 feet wide and at least 80 feet deep, and a length 1.4 km when formally investigated. It runs from the end of a valley at Batchwood Drive to St Albans Road where it has divided to become two smaller dykes/ditches and links to another valley. There is no evidence that the dykes extend across Sandridge Road, or moreover, are connected physically with the system at Wheathampstead. A second smaller dyke, Devils Dyke at Maynes Farm, is 50 feet across and unexcavated. The Devil’s Ditch runs for approximately 840 m between Gorhambury and the River Ver (Wheeler, 14-15). There is the possibility that the later Roman town utilised pre-existing dykes around its south-western boundary. At this point the ditches are large, and where they turn north-west towards the Silchester Gate become two dykes, similar to Beech Bottom Dyke although even more substantial.

1Much of the following is taken from Niblett and Thompson, 2005. Albans Buried Towns and the St Albans Archaeological Strategy.

2The second half belongs to the Verulam Estate and is in private hands; however, the Roman Theatre is accessible for a small fee.

The earliest evidence for occupation in the oppidum derives from the King Harry Lane cemetery excavated by Stead and Rigby between 1965 and 1968. Dating of the earliest evidence for this cemetery depends on the general consensus of c. 15BC – AD 9 (Stead and Rigby, 83), or possibly from the brooch evidence of c. 25 BC (R. Niblett, pers. comm.). This town was a short-lived capital for the Catuvellaunian tribe under king Tasciovanus, before it moved to Camulodunum (Colchester) under Cunobelin, with Verlamion remaining as a tribal sub-capital. Evidence for this site is known from coinage which was minted under the rule of Tasciovanus and bears the VER, VERL, VERLAMIO or VIR mint mark, and appears to pre-date the Camulodunum (Colchester) mint by a decade or so. The move to Colchester was the second one, as the original capital for this area, may have been at Wheathampstead between Devil’s Dyke and The Slad. Although the Roman town is contained within walls, some of which are still visible, the earlier oppidum covers a much larger area, encompassing the slopes and valley bottom from Gorhambury to St Stephens, and opposite including Folly Lane and the lower slopes of the Abbey.

By the early 1st century AD Verulamium had become an important regional centre. The precise character of the settlement at this date is still not clear, but it is of crucial importance for understanding the transition from the pre-/protohistoric to the Roman period. The Roman town of Verulamium is still one of the relatively few Romano-British towns that grew up directly on the site of an existing centre. In the area of St Michaels church and churchyard, the site of the Roman Basilica and Forum, there is evidence for at least one, and possibly two large Late Iron Age and early Roman enclosures. It has been speculated that these represent a royal or religious centre (R. Niblett pers. comm.).

Niblett and Thompson, 2005. Albans Buried Towns

Wheeler, R.E.M. and Wheeler, T. V. 1936. Verulamium A Belgic and two Roman Cities. Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London, No, XI.

Beech Bottom Dyke in the 19th Century as a Rifle Range

“During 1859 there was threat of a possible invasion from France and at a meeting in December it was decided to form a rifle volunteer corps in St Albans. They needed somewhere to practise and Earl Spencer offered them Beech Bottom. A bank was built across it to form the butts and a gap cut in the side to give a maximum range of 600 yards. This was used regularly over the years for both practice and competitions.” (From ‘A Short History of Bernards Heath’, Chris Reynolds, online at www.hertfordshire-genealogy.co.uk).

The local 19th century water colourist Henry Buckingham depicted the scene thus (by kind permission of St Albans Museum).